Daynakin Great Danes LLC

Est. 1974

Championship Quality AKC Fawn & Brindle Great Danes

For Show, Performance and Companionship

Vet Med

The following article is taken from the Seattle Times and I found it to be a good starting point for new Dane owners.

Additionally, it is my strong recommendation that all Great Dane owners carry pet insurance on their dogs, and give serious consideration to an elective gastroplexy.

As a side note, insuring older Danes can be quite expensive. Embrace Pet Insurance offers a policy that covers older purebreds and is very reasonibly-priced. Reviews of this policy can be found at Pet Insurance Reviews

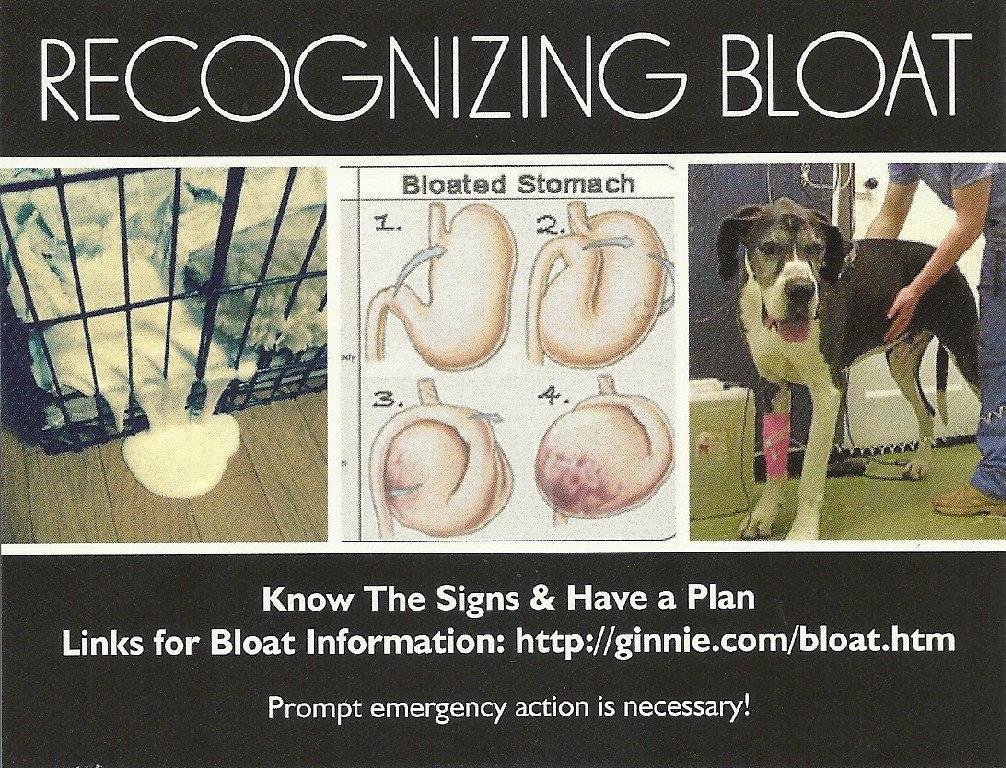

A YouTube video showing an Akita with classic signs of bloat can be seen at Bloat Video.

Link on bloat information.

Veterinary Q&A:

A killer called 'bloat '

Posted by Neena Pellegrini

Greyhounds are among the breeds at risk for bloat. Photo by Inge Grayson

Dr. Amanda McNabb, an emergency-clinic veterinarian, and Dr. Tamara Walker, veterinary surgeon, both at ACCES Animal Specialty Center in Seattle and Renton, answer this week's questions about bloat, a digestive disorder that is among the leading causes of death in big dogs.

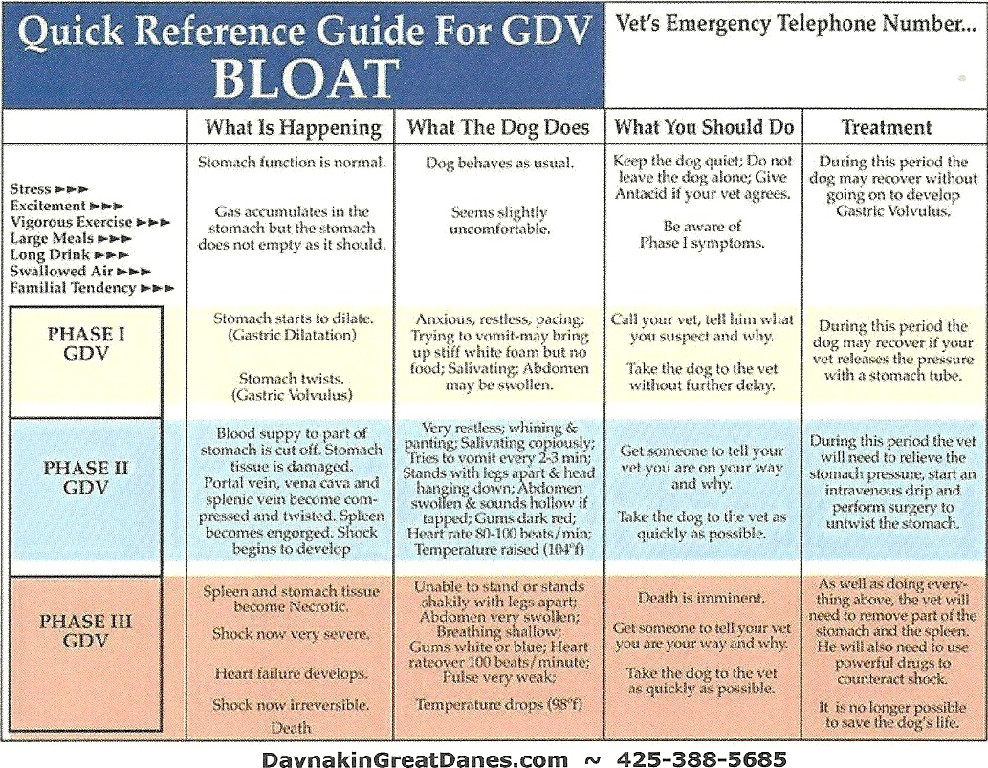

(For a handy quick reference guide on bloat, go to the Great Dane Club of America's website )

Question: Exactly what is bloat?

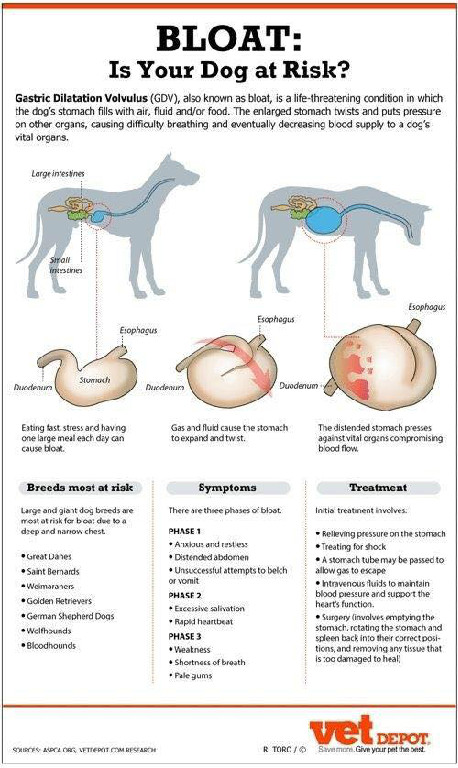

Answer: "Bloat" is a general term for a variety of conditions where the stomach becomes enlarged (dilatation), usually full of gas or excessive amounts of food. Simple "bloat," known as gastric dilatation without volvulus, can vary from mild discomfort to more serious complications, and the stomach remains in its normal position.

The most concerning situation -- and often what people mean when they say "bloat" -- is when the stomach twists (volvulus or torsion) upon itself at the same time. This condition is more specifically called gastric dilatation with volvulus (GDV).

In this disease, the stomach can no longer empty itself, so gas builds up, causing a progressive bloating. As the stomach gets bigger, it becomes painful and compresses other organs and large blood vessels. The rapid twisting can also tear the arteries between the stomach and spleen, cause internal bleeding and damage the spleen. The enlarged stomach eventually stops blood flow to the heart, which results in shock and death.

Without immediate veterinary care, a dog with GDV will die.

We saw 32 cases in our Seattle emergency clinic last year and have seen 145 cases in the past five years.

Question: How dangerous is it?

Answer: GDV is a life-threatening emergency. The overall death rate is about 30 percent.

The earlier the condition is identified and treated, the better the chance of success.

Dogs that are comatose when they arrive at the ER are 35 times more likely to die than dogs that are not. Dogs with a portion of their stomach dead at the time of surgery are 11 times more likely to die.

Three-fourths of dogs treated before their stomachs have twisted are likely to develop bloat again. Not all dogs with bloat will twist their stomachs, but most do, and if the stomach is twisted, without immediate surgery the mortality rate is close to 100 percent.

Death, despite surgery, occurs about 10 percent to 15 percent of the time.

Question: What size dogs are most affected? Does body weight and structure really matter with this disease?

Answer: Any size or breed of dog can develop GDV, but here are some predisposing risk factors: GDV is most common in large-breed -- especially greater than 99 pounds -- and deep-chested (long distance from backbone to sternum but narrow side-to-side) dogs.

Several large studies were published in 2000 looking at more than 1,500 large- and giant-breed purebred dogs over a period of two to five years to establish risk factors for GDV. In these studies there was a 22 percent lifetime risk of having GDV, and a seven percent risk of dying from GDV.

Other identified risk factors include: specific breeds, a first-degree relative with GDV, eating only one meal a day, having a raised feeding bowl and fearful temperament.

Question: Which breeds are most vulnerable?

Answer: Generally, breed risk changes with geography, but Great Danes have a more than 40 percent lifetime risk of developing GDV. At our clinic, the breeds most commonly seen for GDV are Great Danes (14 percent), German shepherds including mix-breeds (14 percent) and standard poodles (10 percent).

Other high-risk breeds can include Saint Bernards, Weimaraners, Irish wolfhounds, Doberman pinschers, setters, Chinese Shar-Peis, boxers, greyhounds and other sight hounds, basset hounds and dachshunds.

Other similar breeds, and any large or giant dogs, may also be at increased risk.

Bryson, a 200-pound Great Dane, goes nose-to-nose with a pony. The Dane, shown with owner Byran Graves of Lake Stevens, is 39-inches at the shoulder. The 5-year-old certified therapy dog died after developing GDV earlier this year. Great Danes are at a very high risk of developing the disease. Photo by Barbara Graves

Question: Why might deep-chested dogs be at a higher risk?

Answer: The causes of GDV are poorly understood, but theories suggest this body shape allows the stomach more room to move freely behind the rib cage. The position of the stomach in these dogs may also change the way it empties.

Question: What are the symptoms of GDV? Are there early signs to be aware of?

Answer: Symptoms generally come on quickly and include nonproductive retching (trying to vomit but producing nothing or only small amounts of saliva), abdominal pain, restlessness and often a tight, distended abdomen.

Nonproductive retching or visible bloating are an indication to seek emergency veterinary attention immediately.

Other common symptoms are productive vomiting (usually fluid and sometimes material that looks like coffee grounds), extreme discomfort and collapse.

Question: How much time do I have to get the dog to the vet? Should the dog be seen by a regular vet or taken directly to an emergency facility?

Answer: This is a rapidly progressive condition, and the difference of an hour can be critical. We recommend going directly to the emergency clinic if you suspect bloat, because very few general practitioners are able to treat this condition surgically and delay of treatment can be fatal.

However, there are things that a general vet can do to stabilize a dog and make it safer for transport to an ER if the ER is some distance away and the general vet is very close by.

Question: What role does exercise, food and/or eating play in the development of bloat?

Answer: The causes of GDV are poorly understood, and there are many theories. Many of these have not held up in scientific testing.

In recent studies, factors associated with food that were found to significantly increase risk included feeding one meal a day and feeding from an elevated bowl. Many other factors have been investigated in small studies, but food texture and type has not been strongly correlated with GDV so far.

Popular theories also have included exercise after a large meal and drinking large amounts of water with a meal. But these have not been consistent in scientific studies.

Logically, having a large meal or drinking a large volume of water and immediately exercising could increase the risk of bloat, and it is generally recommended that owners with dogs of high risk for bloat do not do these things.

Question: We've heard pro and con on raised food bowls.

Answer: Theories had suggested raised food bowls as a prevention. However, a study published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association in 2000 found that raised food bowls actually significantly increased the risk in large- and giant-breed dogs (up to 52 percent). Based on this, many now advise against raised food bowls for high-risk breeds, unless necessary for other medical conditions.

Question: What role can heredity play?

Answer: Heredity may be one of the biggest factors involved. Because purebred dogs of specific breeds have higher risks, there is strong evidence of a hereditary role. Recent studies also show a much higher risk in dogs who have had a close relative experience GDV.

Question: Can stress cause it or make it worse?

Answer: Yes. Dogs that are nervous have been shown to be at higher risk, and stressful situations, such as boarding, hospitalization, other illness or surgery or travel, may bring on an episode of GDV.

Question: Can any tests be done to determine if my dog is vulnerable?

Answer: Because the causes are poorly understood, there are no recommended screening tests now.

Any dog of a high-risk breed (or shape), especially if a close relative (parent or sibling) has experienced GDV, should be considered vulnerable.

Ansel, right, suffered GDV during a cross-country road trip. His owner, Dr. Amanda McNabb, says vets were able to get him into surgery quickly, and he did well. Photo by Amanda McNabb

Question: If my dog is gassy, is that an indication he/she might have a problem with bloat or the potential to develop it?

Answer: Dogs that already are in high-risk categories that also have a history of chronic gastrointestinal disease or a distended stomach have been shown to be at increased risk. There are lots of other reasons a dog may pass more gas than other dogs, so this is a very nonspecific sign.

However, veterinarians frequently recommend medications to decrease gas and increase emptying of the stomach for high-risk dogs with signs of gassiness or with other stomach upset.

Question: We're read about gastropexy -- stitching the stomach to the chest wall to prevent bloat. What can you tell us about it -- does it prevent bloat and can it be done in conjunction with spaying? Is it a procedure you would recommend?

Answer: Gastropexy is the surgical procedure that permanently attaches the stomach to the inside of the abdomen on the body wall. It has been shown to decrease the risk of GDV by more than 92 percent.

The idea is that a stomach that is permanently "stuck" to the body wall cannot twist. It cannot prevent the "bloat" or dilatation part of GDV, but it can prevent the dangerous twisting, or volvulus.

It can be performed at the time of surgery to correct a GDV, or it can be performed prophylacticly to prevent GDV from happening. Gastropexy can be done as an open abdominal procedure alone or at the same time as another procedure such as a spay. It also can be performed with a laparoscope, which uses a small camera to perform the procedure through several much smaller incisions.

Depending on how and where the procedure is performed, cost is about $1,500-$2,500.

Recovery is rapid, and the risk of complications is very low, regardless of whether the procedure is performed open or with a laparoscope.

Recovery is generally more rapid with laparoscopic procedures, where dogs need to have their activity restricted for about one week. If the procedure is performed open, activity is usually restricted for about two weeks until sutures are removed.

Gastric dilatation without torsion and GDV most likely have the same underlying cause, and, therefore, it is also prudent to consider gastropexy in all patients with distention without twisting. This should be performed as an elective procedure shortly after patient recovery from the episode.

Given the extremely high lifetime risk of GDV for Great Danes, prophylactic gatropexy is recommended in this breed. Other dogs should be considered on an individual basis.

Question: What does a vet have to do to stop the episode from becoming critical or, if it has become critical already, what has to be done to save the dog? Is surgery always required?

At right, an X-ray of the stomach of a dog with GDV. Photo courtesy of ACCES

Answer: If a dog has simple "bloat" without volvulus, he/she may not be critical. However, prompt medical treatment is recommended to prevent volvulus. It also is difficult to distinguish between the two without X-rays.

If GDV is present, the patient is always critical and requires immediate attention. Emergency treatment is a must because the dog could die within hours.

This involves a combination of decompressing the stomach with a tube or a large needle, IV fluids for shock and pain medications, followed by emergency surgery to untwist the stomach and perform gastropexy.

If the stomach is de-rotated but gastropexy is not done, most of these dogs will have GDV again.

Depending on how advanced or severe the individual case, some dogs also require removal of portions of the stomach or removal of the spleen.

Question: What factors lead to a poor prognosis?

Answer: There are many potential complications from GDV. The most serious include shock/collapse/death from lack of return of blood to the heart and toxins in the blood, heart arrhythmias, death of the stomach wall caused by stretching and lack of blood supply, aspiration pneumonia from inhaling vomited stomach contents and a very distended stomach postoperatively that is unable to move food through in a normal manner.

Many veterinarians will recommend tests, such as plasma lactate levels, clotting times and chest X-rays to help rapidly assess risks.

Delayed treatment may increase the likelihood of these factors and therefore cause a poor prognosis.

Question: How much can this cost to treat? A general range.

Answer: This can vary widely based on pet size and development of complications. We generally quote about $3000-$5,000 for diagnosis and treatment of GDV.

Drs. Amanda McNabb and Tamara Walker

For more information on bloat, go to veterinarypartner.com

McNabb received her veterinary degree from the University of Tennessee in 2002. She did small-animal and surgical internships at Cornell University. She has six years of veterinary emergency experience as well as experience in general veterinary practice in the Seattle area. Her special interests include the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association's Field Services work, helping at spay/neuter clinics and shelter medicine. At home she has various pets, including one dog, two cats, snakes and some frogs.

Walker graduated from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in 1995, completed an internship in small-animal medicine and surgery at the University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario in 1996, and completed her surgical residency and Master's degree at Washington State University in 2001. She is a board-certified small-animal surgeon with more than 10 years experience, six of them at ACCES. She has a special interest in surgical oncology as well as complex cases requiring support from all aspects of the hospital. At home, she has one dog and two cats.

For information on a bloat study being done, please visit my "Health Studies" page.